Here is one stunning visualisation of horses left to us by the Romans. These are the famous horse statues from St Marks, Venice.

These beautiful bronze horses were made by an unknown Roman artist. Surely we can say that the grace of the statues captures the artist’s admiration for the beauty of the horse. These figures seem full of restrained strength and bursting energy, about to bound away from the pedestal. The artist has captured a lively solidity in the animals, the bronze almost breathes. Along with grace and beauty, the artist conveys strength and power. These are the qualities that the horse has brought over many centuries to the service of human history.

Human history has been carried by the horse. Since mankind first domesticated the horse, until the time of the Industrial Revolution, the story of human development was intimately involved with the horse. For transport, agriculture, war, communication, sport, and leisure, the horse was the unmatched carrier of mankind’s ambitions. It was, above all, in the field of communication that the horse most fully participated in the expansion and administration of the Empire. Without good communication across varied geographical areas, no Emperor could hope to rule efficiently. It was the horse that sustained communication across the Empire. From Britain to Parthia, from Libya to the Danube, it was the horse that kept the complex Roman postal system working.

The Roman Imperial postal service was so efficient that, in exceptional circumstances, it was able to carry letters from the province of Britain to Rome in ten days. Within a short time after the invasion of 43AD, Britain was connected to the imperial postal system known as the CURSUS PUBLICUS. Don’t be misled by the word PUBLICUS, it was far from a public service. Remember that the word PUBLICUS has the special connotation found in the formula RES PUBLICAE which simply means PUBLIC THINGS. But RES PUBLICAE was later transformed into REPUBLIC, in other words the name that designates THE STATE. Thus the CURSUS PUBLICUS was a state postal system which could only be used by top officials, army officers commanding in the field, friends and family of the Emperor and the Emperor himself. This state postal service was made up of a network of messengers and relay posts which would provide a change of horses at stipulated distances. Couriers travelled about fifty miles a day (one Roman mile = 1000 paces) but much further in extreme circumstance.

There was a severe penalty for anyone caught using the service frivolously. Ordinary Romans had to use alternative methods of delivery such as travelling merchants, traders and servants

Though never great natural horsemen, like the Goths and Huns, the Romans saw that the proper use of cavalry could be decisive in battle. Their fundamental military unit, adopted from the Greek phalanx, had always been the highly-drilled infantry cohort. Disciplined ranks of men, using the gladius or short stabbing sword with deadly effect, had always been the pride of Roman military might and the keystone of its success. However, when faced with enemy cavalry, especially the expert horsemen of Parthia, who could gallop flat out while turning in the saddle to shoot an arrow behind them with fatal accuracy, the Romans re-thought the use of the horse in war and adopted cavalry to assist the infantry legions. Thus the ala, or mounted wing came into being. These were most often made up of auxiliary troops. Strange to say, for a people who made great advances in technology (concrete, arched vaults, aqueducts, piped water, signalling, roads, sewers etc.), the Romans never invented the stirrup and therefore the usefulness of the horse in mounted combat was never as great as among medieval knights, for example, who could use stirrups as a purchase for forward thrust in mounted hand to hand combat, or massed charges with lances.

In the Roman world, most of the heavy haulage work would be done by oxen or mules. Mules are hybrid animals, half donkey, half-horse, extremely hardy and strong but incapable of reproducing themselves. They were used for transport of goods and baggage, haulage and agricultural work. Some horses were used in this way but because a horse is much less tough than a mule, its workload was often lighter. The best bred horses took part extensively in peace-time activities such as festivals, games and triumphal processions.

The fastest and strongest of the horse breeds would be trained for the Chariot Racing Circus, where a good lead horse could become something of a celebrity in his own right. Athough most Roman charioteers (called aurigae or agitatores) began their careers as slaves, those who were successful soon accumulated enough money to buy their freedom. The four Roman racing companies or stables (factiones) were known by the racing colors worn by their charioteers: Red, White, Blue and Green. Fans became fervently attached to one of the factions, proclaiming themselves “partisans of the Blue” in the same way as people today would be supporters of football teams. There were usually twelve races scheduled for a day, though this number was later doubled.

The charioteers drew lots for their position in the starting gates; once the horses were ready, the white cloth (mappa) was dropped by the sponsor of the games. At this signal, the gates were sprung, and up to twelve teams of horses thundered onto the track. The strategy was to avoid running too fast at the beginning of the race, since seven full laps had to be run, but to try to hold a position close to the barrier and round the turning posts as closely as possible without hitting them. There were many ways that teams from one stable could foul their opponents during a race, and sometimes even before it started, it is known that attempts were made to dope or poison horses and charioteers. Then, as now, big money sport could be unscrupulous. Fanatical partisans sometimes even resorted to magic, seeking to “hex” the rivals of their favorites by writing elaborate curses on stone or clay tablets.

One of the greatest Chariot Racing Drivers of all time was a young man called Scorpus who lived at the end of the first century AD. In his day he was a glamorous celebrity, petted by the aristocracy, fought over by idolising women, invited to prestigious dinner parties, fêted, followed and drooled over like a modern day ‘star’. Perhaps deservedly so, for in his short career he won 2,048 victories. Since every chariot race was a gamble against death, Scorpus put his life on the line at least 2,048 times. But then his luck ran out.

When he died at the age of only twenty-five, all Rome was shocked. The whole Roman populace mourned in stunned disbelief. Many stood to lose money. The poet Martial, with his finger on the pulse of the public mood as ever, wrote an epitaph for him:

I am Scorpus, the glory of the noisy circus, the much-applauded and short-lived darling of Rome. Envious Fate, counting my victories instead of my years, and so believing me old, carried me off in my twenty-sixth year. [Martial, Epigrams 10.53]

It is not known how Scorpus died, but it is likely that he was killed in one of the frequent crashes of the Circus, which the Romans called ‘naufragus’ or ‘shipwreck’. But it was not only the drivers who could attain fame and be immortalised in art.

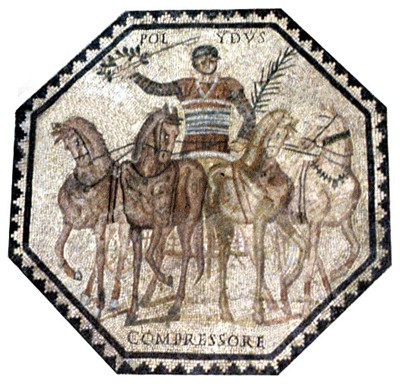

Compressore is the lead horse of the chariot team driven by Polydus, a charioteer from the red faction. This mosaic is the centrepiece of a large floor decoration from the imperial baths in Trier, Germany, dating from the mid third century AD. The palm frond and laurel wreath which Polydus is carrying, indicate that the team has just been victorious. The lead horse was the most important member of the team. He would be experienced in racing and know where to place the team on the track almost without the charioteer’s direction. Charioteers were usually in the habit of tying the four reins around their waist, an extremely dangerous practice in the case of a crash because they could be pulled out of the vehicle and smashed against the barrier or dragged under the hooves. The lead horse worked with the three other horses and the charioteer as a crucial member of the team, setting the pace or changing course, trying to keep an even ‘pull’ on the chariot and responding to the charioteer’s instructions. Compressore is a sporting horse from 2,000 years ago whose name is immortalised in traditional Roman art.

In literature, too, the Romans acknowledged their debt to the horse. When Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro) came to write his mythical epic of Rome, the Aeneid, around 20 BC, he movingly evoked the special bond which battle forges between a horse and a rider.

In a passage towards the end of Book X, he shows a warrior king called Mezentius, who has just lost his own son, Lausus, killed in battle by Aeneas the Trojan founder of Rome. Wounded himself, Mezentius asks for his horse to be brought.

‘This horse was his pride and his consolation, and on him he had ridden home in triumph from all his wars. To him, companion in his sorrow, he spoke, beginning with these words: “Rhaebus, our lives have been long – if that word can be used of anything possessed of mortal creatures. Today either you shall be joint-avenger with me of Lausus’ agonies…or …you will die with me, for I know, valiant friend, that you will never submit yourself to a foreigner’s commands or a Trojan master.”’

[Aeneid Bk X, trans W.F. Jackson Knight, Penguin Classics, 1956, p. 277]

Notice the pathos, the amount of feeling and emotion, that the horse is given: sorrow, courage, a sense of triumph. Equally the horse is assigned human passions as he is invited to ‘share’ in the revenge. Again, there is a sense of the inseparability of their companionship as they will either ‘jointly avenge’ or ‘die together.’ The horse is given will and intelligence in the idea that he would ‘never submit’ to have another master. The horse is, above all, amicus, friend. To the Romans amicus was a very special relationship of close reciprocal trust and understanding. No relationship was as special to a Roman male as amicus, which was like the sharing of a soul. Virgil’s choice of word in this context is very forceful in showing the spiritual bond between Mezentius and his horse, Rhaebus. In this brief sketch Virgil evokes with great sympathy the friendship that could develop between man and horse in war.

What happens to Rhaebus? Sad to say, he is struck in the forehead by Aeneas’s spear:

‘the animal reared up and hung there, his forefeet pawed at the air, his rider was unseated: then the horse came down on top of him, pinned him and lay there, its shoulder put out and its head drooping.’

Rhaebus dies like a warrior of epic, nobly and with honour, and within a few moments his master’s throat is slashed by Aeneas. They lie together to this day in Book X of Virgil’s Aeneid.

It is surely significant that Rome’s greatest epic poet gives this marvellous little cameo to the horse. No other animal is treated with quite so much human tenderness. Perhaps something of this spirit of admiration, esteem, even veneration, for the horse is discernible in the workmanship of the Roman horse statues above. Here, cast immemorially in bronze, is the epic sense of mankind’s friendship with the horse which Virgil depicts in the Aeneid.