What we most often mean by ‘history’ is historiography, written histories. But the historical narratives of the Anglo-Norman period are often unreliable, partisan and fraught with interpretive hazards. To historians of that period, the differences between history and fable, sacred legend and other forms of imaginative writing are not strongly established. They are all concerned with telling memorable stories – and this, too, is the main concern of the historical novelist. It might even be the case that the modern historical novelist is at more pains to ‘get the facts right’ than the early historians. For example, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, written in Latin and finished about 1136. Although called a ‘History’, it is rather a compilation of legend, fabulous tale, and imaginative invention. This supposed ‘history’ traces the story of the Kings of Britain from mythological beginnings in ancient Troy and portrays figures such as King Lear, Cymbeline, King Arthur and Merlin. It has little veracity as history but has remained a powerful source of romantic stories, used by such writers as Thomas Malory, Shakespeare, Dryden and Tennyson.

But – and this, I think, is very interesting – Geoffrey of Monmouth claims that he translated the book out of an ‘ancient British language’ as though he felt the need to connect his book with some ‘original’ in order to give it an authentic status. As this was not the ‘original’ of historical fact, he claimed it as deriving from the original of a ‘native’ language (probably Welsh), which is also doubtful. The idea implicit here is that you have to anchor your historical narrative in some ultimate ‘original’.

Much more reliable than Geoffrey are the three great history writers of the time, the best sources for this period: Orderic Vitalis, William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon. They don’t write in English – they write in Latin – but all are of mixed parentage and have English and Continental connections. But these writers, along with with their contemporaries, offer us a paradoxical state of affairs – an extensive legacy of written texts of uncertain reliability.

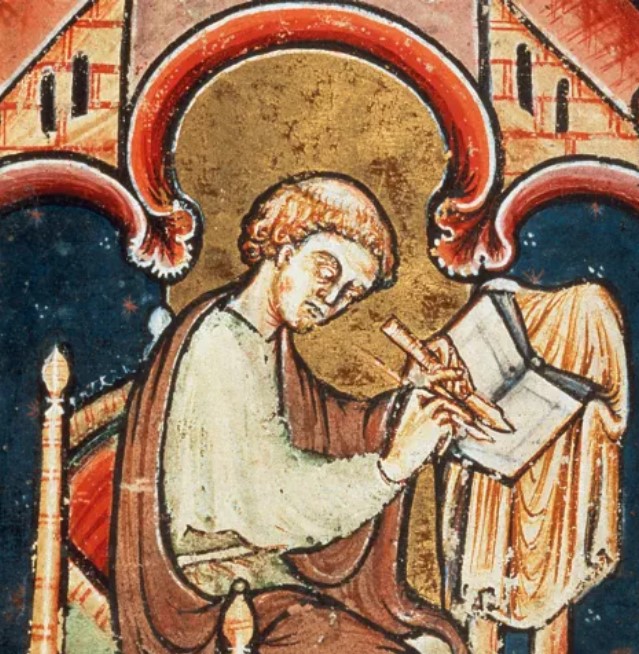

Orderic Vitalis was born in or near Shrewsbury in 1075 and was sent to Normandy in 1085 to become a monk at the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Évroult in Normandy where he remained for the rest of his life. His work, Historia ecclesiastica is generally considered the most valuable for Norman, English, and French history in the period 1082–1141.

William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Regum Anglorum, Deeds of the English Kings was completed in 1125. William was born of mixed parentage about 1095 and entered the monastery at Malmesbury. At that time the Abbot was a Norman monk from Jumièges. So in a community of mainly English monks led by a Norman Abbot, William of Malmesbury got first hand experience of integration and perhaps this made him alert to the difficulties of interpreting recent history.

The historian or chronicler, even though he may be living very close to the time about which he is writing, has to rely on earlier works whose veracity cannot be established. This, too, is the situation of the modern historical novelist but the novelist is in the happy position of being able to fill in the blank spaces with imaginative invention.

Henry of Huntingdon (1088-1157) is the third of the trio of major Anglo-Norman historians. Again he was of mixed parentage. But perhaps more importantly, he was the first of the great historians who was not a monk. He was a secular priest and was married, as many priests at that time still were. (One of the themes explored in The Domesday Murders)

All these historians identified themselves as English in some way and showed a strong attachment to the country, but they did not write in English and all had Continental ancestors. Their divided allegiances meant that their judgements could be complex and nuanced. But, as Christian historians, they were shaped by the historical understanding that God played the dominating role in history. The purpose of history was to teach moral lessons.

And one of the greatest of those was that defeated peoples and losing sides in war were being punished by God for some sinful lapse or moral degeneracy. It was the historian’s job to warn about the consequences of God’s anger and berate people for their sins.

So, when we read these historians we have to come to them with some scepticism – as we might do to a tale or fable. There was at this time no critical analysis of the historical process, no real commitment to check facts, question sources, collect data, travel to interviews etc. though some honourable attempts were made.

History was largely written from the perspective of God’s unfolding plan, his punishment of wickedness, his favour of the righteous. Or perhaps historians would be writing in celebration of a particular individual –a saint, a king, an Abbot.

All the contemporary or near-contemporary historians of the conquest were using the events of the conquest to provide a framework for their own preoccupations. There was, in others words, no attempt to analyse the dynamic of history.

The way historians constructed the Conquest and its aftermath was bound up, too, with their own views of literature. After all, history was considered to be a part of grammar or rhetoric. History wasn’t a ‘disciplina’ in its own right but a branch of the trivium- grammar, logic and rhetoric. These historians would be influenced by whichever classical models were they taking for their own practise. They would also be influenced by their allegiances, their political and religious affililations, or they were concerned to celebrate a patron. Thus, many factors converge in their writings – not simply the matter of laying bare historical truth. Nevertheless it is to these gifted and vivid writers that we owe our vision of the Anglo-Norman period.