Among items listed in the Domesday Book were the mills with a total of over 6000 mentioned. These would have been watermills, or perhaps animal powered mills – the survey was completed before the introduction of windmills. Many places are listed as having a fractional number of mills, which presumably came about because the “mill” was shared, or somehow only taxable on part of it. It’s likely that a mill referred to the machine, rather than the building itself – so a single building containing multiple sets of mill stones would have been recorded as several mills.

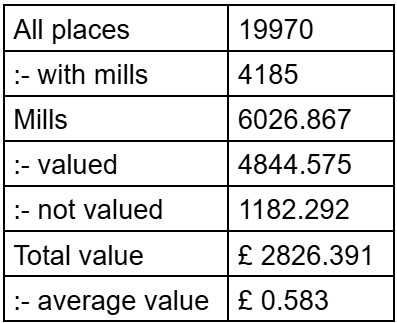

Data extracted from work done by John Palmer and his team at the University of Hull (who created the Domesday Explorer CD-ROM) suggests that there was a significant presence of mills in the country in 1086.

The Domesday Book was an incomplete survey so there are errors in the raw data. In other words the figures should be treated as an indication rather than as substantial fact. No record from the period can really be treated as valid with 100% reliability.

Overall Figures

The first thing to notice is that some mills are valued and some not. The value of a mill probably comes from the millstones within the mill and the amount of revenue it could generate rather than from the wooden building itself. A lord would own the mill as property on his land and would appoint a miller to oversee its daily functioning. Generally, the lord would cause all the people in the area to grind their grain at his mill for which they would pay a fee. This was underpinned by what were called ‘soke rights’ the right of the lord to have exclusive and chargeable use of the mill. Thus the revenue raised in this way was a sort of tax.

The Miller is a significant figure at this period and long afterwards. Chaucer’s Miller’s Tale, suggests various characteristics associated with millers who might be projected as comic figures, perhaps vulgar and overweening, or else tyrannical and brutal. Rarely is a Miller portrayed as a quiet, well-disposed type of local. Pity his situation, trapped between his duty to the overlord whose demands he must fulfill, and the resentment of the villagers who feel constantly overcharged for their use of the mill.

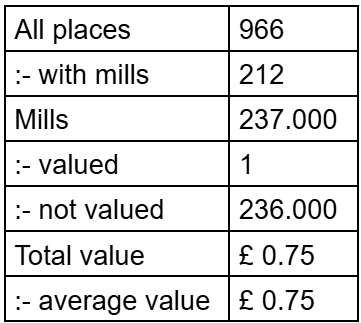

Essex

To take just one case in my own county of Essex. In the Domesday Book the mill at Little Maplestead in Essex is mentioned as ‘not valued.’ (This reference comes from Domesday Book, Penguin Classics, eds. Williams and Martin, published 1992, p. 1033, 4th column).

Little Maplestead I mill not valued. Landowners : Warenne has mill only

A further reference in the Domesday Book adds a little more information (p. 1046).

Osmund holds Great and Little Maplestead from John fitz Waleran but the mill is held by William de Warenne as pledge…

From this reference it is interesting to see how a mill may be held separately from the rest of the lordship. Here the mill is tantalisingly suggested to have been in dispute or has been assigned to William de Warenne in pledge for some service owed or due, while John fitz Waleran is the overlord of both the Maplesteads. This suggests that mills were particularly valued separate properties.

As might be expected, mills were built by wealthy lords or monasteries. In exchange for the expense and responsibility of constructing, maintaining, and running the required number of mills for each community, the people were obliged to support the mill by taking their grain to it and paying one sixteenth of their harvest in payment for its usage. Sometimes households got around this by keeping a small hand mill, but often such hand mills were forbidden.

The position of miller, especially in remote rural settings, was typically hereditary. He might be considered a serf under the lord, and not a free man. But he might be a free man obligated to a lord. Millers were notorious for being dishonest–sometimes stealing the grain they were entrusted with, or collecting inflated toll payments. The lord’s grain, of course, was ground for free and took priority over that of anyone else.

Mills were used for other purposes besides grinding grain. For example, to extract oil from things like nuts, seeds, or olives. In places where there was a large wool industry, mills were used for the fulling process. In later years windmill technology had another purpose as a defensive device against attacking armies. Their immense height allowed them to be used as a lookout tower, or even a fort. Sometimes they were built directly onto a castle tower.

In general terms, the Norman Conquest introduced ‘the feudal system’ to the country and ‘soke rights’ forced everyone to have their corn milled at the mill owned by their Manorial Lord. In some parts of the country, this custom stayed in use until as late as the 19th Century.

The Miller in the Later Middle Ages

In Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’, the figure of the Miller is often described as a peasant or tradesman. He was a free man but not a wealthy one. He was neither rich, powerful, nor influential. Since he was in a good position to overcharge or steal grain, he became a figure of suspicion. In ‘The Canterbury Tales’, the Miller, who is very drunk, announces that he will tell a story about a carpenter. He then proceeds with a lewd and vulgar tale, mocking the carpenter and revealing himself as coarse and rambunctious. Oswald, the Reeve, then objects to the Millers’s tale because he was once a carpenter. Having since risen in the social hierarchy he does not enjoy the mockery.

In Chaucer’s day [d.1400] a Reeve was a servant of the lord of the manor and was sometimes elected from among the peasants. Like the Miller, he was an important figure in the post Conquest organisation of labour to produce wealth from the countryside. He had the job of overseeing peasant labour on the demesne, representing his lord’s interests in local disputes, attending the manor court and keeping financial accounts. He was the first practitioner of Estate Management and occupied an important position of trust but, like the Miller, was often hated by the poorer peasantry.

The Domesday Murders dramatises some of this difficulty in the character of Gurth the Miller.

Little Maplestead Church, Essex

As well as being the only place in Essex to have a mill recorded in Domesday, Little Maplestead is distinguished by having a remarkable church. It is one of only four churches in the country to have a circular nave. This was not a whim on the part of its builders. Such churches were only built by the Knights Templar and the the Knights Hospitaller (now the Knights of St John ), both of which orders were emulating the fourth century Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem which they saw when taking part in the Crusades. Of the four round churches in England, only the Temple Church in London and Little Maplestead are associated with the two orders. As its name implies, the Temple Church was built by the Templars, leaving Little Maplestead as the only round-naved church in England associated with the Hospitallers.The village and manor were given to the Knights Hospitaller in 1185 in the reign of Henry II. They built a commandery across the road from where the church is situated and then a church for their community to use. It probably replaced an earlier Anglo-Saxon church.

Little Maplestead once had a Knights Hospitaller establishment called Little Maplestead Preceptory.

To sum up: the round parish church dedicated to St John the Baptist, is one of only four medieval round churches in England now surviving. The circular nave has an arcade of six bays. The church dates from around 1335 but was practically rebuilt between 1849–55.

So Little Maplestead had a mill at the time of the Conquest, which was under the control of William de Warenne who fought with the Conqueror at Hastings. This man’s son, also William de Warenne, succeeded to his father’s lands and privileges but did not always render good and faithful service to the Conqueror’s successor kings, William Rufus and Henry 1st. Something of his turbulent story is told in After the Arrow.