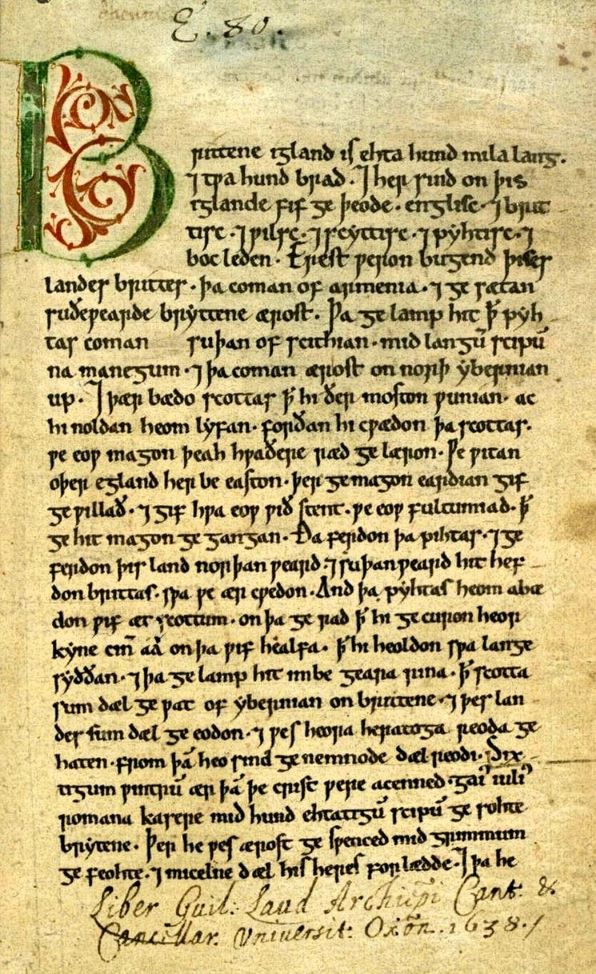

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals chronicling the early history of England from the perspective of monastic insiders. Written in some of the great monasteries of England: Winchester, Peterborough, Abingdon and Worcester, by wholly anonymous annalists, the MS vary and are discontinuous and in many hands, but were probably begun about AD 891 at Old Minster, Winchester.

One of the most remarkable things about these early manuscripts is that they were written in English. It means that English prose was considered of sufficient status to become the appropriate medium for a documentary record of year by year happenings in England. This makes the Anglo Saxon Chronicle the first continuous national history of any western people to be written in their own language.

Some Extracts from the Peterborough Manuscript for the Year 1100

In this year the king William held his court at Christmas in Gloucester, and at Easter in Winchester and at Pentecost in Westminster. And at Pentecost at a certain village in Berkshire blood was seen to well up from the earth as many said who must have seen it. And after that, on the morning after Lammas Day (2nd August) the king William was shot with an arrow in hunting by a man of his, and afterwards brought to Winchester and buried in the bishopric, the thirteenth year after he succeeded to the kingdom.

The above passage is representative of the style of the chronicle, a focus on dates and a bare collection of facts, interspersed with hearsay and local rumour. There then follows a fairly comprehensive condemnation of the King’s practices in humiliating the church. Here the chronicler takes a violently pro-church anti-monarch stance which would be in keeping with general monastic and ecclesiastic opinion at the time. King William did undoubtedly keep churches vacant, refusing to appoint bishops and abbots and siphoning off the church’s wealth into his own coffers. This antagonised churchmen and caused deep offence.

And thus on the day that he fell he had in his own hand the archbishopric of Canterbury and the bishopric of Winchester and that in Salisbury and eleven abbacies, all put out at rent.

In other words, the view from the monasteries was that the king was stealing from the churches on a massive scale.

And therefore he was hated by well-nigh all his nation, and abhorrent to God, just as his end showed because he departed in the midst of his injustice without repentance and any reparation.

These extracts give a fair flavour of the sort of political story coming out of the monasteries. And to be fair there was some truth in it, William II was high-handed in his treatment of the churches and probably not very pious in his personal life. There was plenty to carp at, to be sure. But the king was not entirely the villainous, oppressive dyed-in-the-wool tyrant that he is painted. The Peterborough writer despatches William in a sentence or two:

He was killed on the Thursday and buried next morning. And after he was buried those councillors who were near at hand chose his brother Henry as king.

And straightway he gave the bishopric in Winchester to William Gifford and afterwards went to London and [ ….] Maurice of London consecrated him as king and all in this land submitted to him and swore oaths and became his men.

It is more probable Henry chose himself as king and acted with lightning speed to quell any dissent by making an ecclesiastical appointment. What happened was probably closer to a coup than an election.

You can find more about the story of the king’s death and the extraordinary events that followed in After the Arrow.